IMI contributed to development of the most promising Ebola vaccines, helping to bring them closer to regulatory approval

Update: On 31 October 2019, an international consortium announced the start of a trial of the J&J vaccine in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Read more here.

Why is there still no licensed Ebola vaccine?

Ebola vaccine research has been ongoing for decades. The sheer scale and urgency of the outbreak in 2014-2016 in West Africa kicked that research into high gear, and funded projects that conducted or contributed to clinical trials on the two vaccines that showed most promise. The vaccines seemed to work, but more complete data about the exact mechanisms of protection, as well as safety and durability, were needed before either vaccine could be licensed.

The Merck vaccine

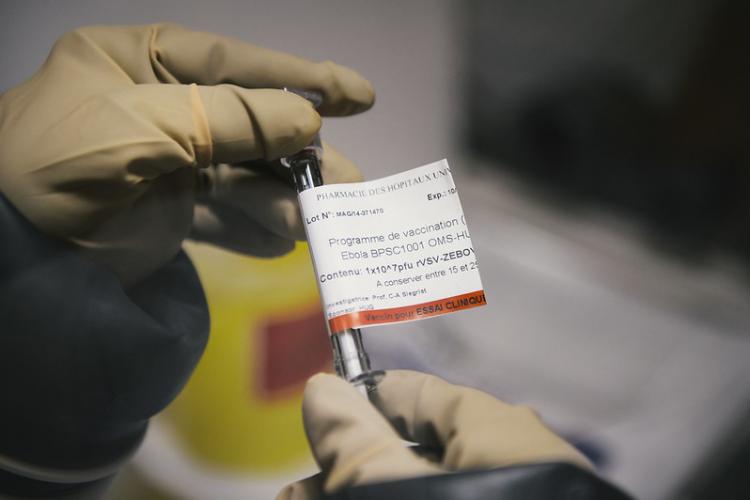

rVSV-ZEBOV-GP, the ‘Merck vaccine’, as it’s known, was developed by the Public Health Agency of Canada in the early 2000s. It consists of a live but harmless vesicular stomatitis virus – a virus that usually targets horses and other livestock - engineered to carry and express a gene coding for the Ebola surface glycoprotein.

IMI launched the project VSV-EBOVAC in 2015 to get more data on the type and strength of the immune responses triggered by the vaccine. They were able to identify potential side effects (namely, self-limiting arthritis) and gather data on the ways in which antibodies bind to the virus. They were also able to show that antibody responses are still going strong at least two years after immunisation. The results of their work were published in Science Translational Medicine in 2017 and in Lancet Infectious Diseases in 2018.

Video: IMI carried out clinical trials of two of the most promising Ebola vaccines.

Awaiting licensing

The Phase II clinical trials of the Merck vaccine were carried out in Guinea during the West African outbreak, and it was shown to be up to 100% effective using a ‘ring vaccination’ strategy. While IMI was not involved in these trials, the VSV EBOVAC and VSV EBOPLUS projects contributed to the existing clinical trials by extending follow-up visits in order to collect more human samples and data. This allowed researchers to perform in-depth immunological and molecular analysis to help understand the vaccine’s mode of action and expected duration of protection.

“It was probably the first time that in such a short time we went from no vaccine to using a vaccine to control an outbreak."

The VSV-EBOVAC consortium organised and got to work very rapidly. According to Professor Donata Medaglini, professor at the University of Siena and Vice-President of the Sclavo Vaccines Association who coordinated the project, “It was probably the first time that in such a short time we went from no vaccine to using a vaccine to control an outbreak. IMI was able to mobilise the researchers and launch the call extremely quickly.” The projects generated a wealth of safety and immunogenicity data on the vaccine that may strengthen the chances of gaining regulatory approval and ultimately, licensing.

The Merck vaccine is currently being deployed in the Democratic Republic of the Congo by the World Health Organisation under ‘compassionate use’, and is playing a big role in controlling the spread of Ebola there. It has already been submitted for license with a likely approval before end of 2019.

The J&J vaccine

The ‘J&J vaccine’ is an investigational Ebola vaccine regimen developed by Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies of Johnson & Johnson. It’s is a two-dose regimen made up of a first dose of Ad26.ZEBOV and a second dose of MVA-BN-Filo. IMI funded a number of different consortia to carry out the safety, efficacy and immunogenicity studies of the vaccine regimen.

The projects intended to carry out different phases of clinical trials concurrently, in order to speed up the development timeline. Rodolphe Thiébaut, professor at the Bordeaux University, deputy director of the Inserm Bordeaux Population Health research centre and coordinator of the EBOVAC2 project (which carried out the phase II trials) says: “Normally you would wait until phase I trials are finished before starting any phase II trials. It’s a risk and a challenge but it was the largest epidemic ever and it was important to act extremely quickly.”

The aim was to get to phase III trials in three years. Fortunately, the outbreak in West Africa got under control. This meant that clinical efficacy testing was not possible, however, because the outbreak ended. The planned clinical studies were modified to adjust to the situation. Recent reports suggest that the J&J regimen is being considered for deployment in the DRC to target at-risk populations in areas that do not have active Ebola transmission, as an additional tool to extend protection against the virus.

More stories in the Ebola series

How do you prepare for a pandemic? by Pierre Meulien, IMI Director

Ebola can now be detected in 15 minutes. Here's how the diagnostic tests work.

Related

"Second Ebola vaccine to complement “ring vaccination” given green light in DRC" - WHO newsroom

Plasma signature, safety and immunogenicity of the Merck vaccine - Science Translational Medicine

Study on antibody persistence of the Merck vaccine - the Lancet